THE FABLES

For the moral philosopher in Ramsay, the humble fable with its aura of the schoolroom was a perfect mask. It empowered him to preserve his appearance of social and political equanimity while scolding his betters, just as it had enabled La Fontaine to mock Louis XIV’s grand siècle while contriving to survive in it.

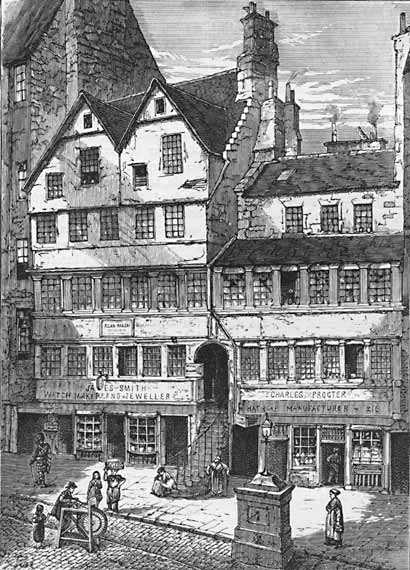

His twenty-nine fables were published between 1722 and 1730, but most, if not all, were written in a single creative outburst in late 1721 and early 1722, around the time he left off wig-making and set up business as a bookseller in a fine shop near the Cross-well in Edinburgh's High Street.

His fables were naturally intended for school consumption, but also for a much broader readership. This short comic form issued in penny sheets and sixpenny pamphlets was perfectly suited to his stance as a poet-philosopher aiming at uplifting his readers while entertaining them in their native tongue. Along with his other self-published works in Scots and English, it helped to earn him the esteem of his fellow citizens during his lifetime (and a statue on Princes Street a century after his death).

RAMSAY'S SCOTS

Sir Walter Scott tells how, in the wake of the Porteous riots in 1736, Alexander Wilson, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, was summoned to the bar of the House of Lords. The Duke of Newcastle having demanded to know what kind of shot had been issued to the Town Guard, Wilson answered "Ow, just sic as ane shoots dukes and fools wi". Fortunately, the Duke of Argyll was able to explain to the Noble House that the Lord Provost had meant, properly rendered into English, "ducks and waterfowl".

The old language "broke down" (in David Murison's words) in the generation after Ramsay's because the members of the so-called Scottish Enlightenment, whose peculiarities made them a laughing stock in Dr Johnson's London, became ashamed of their heritage. Hume and Boswell, for instance, did their utmost to erase their Scots vocabulary and pronunciation. By 1750, the last generation of educated native Scots speakers was in or on the verge of the grave, and Ramsay's attempt to champion both the survival of Scots as such and the emergence of a new British language combining Scots and English had failed. After him, though Fergusson still wrote in a distinctively Scottish idiom, Burns knew he was using what was generally held to be a dialect of English.

In any case, speaking the language was only one side of the issue. When the first free presses were set up in Scotland after 1695, writers of Scots were or felt obliged to adopt the anglicized orthography devised by the compositors brought in from England and the Low Countries to work them. Ramsay himself, schooled in English and raised by an English grandfather, anglicized his spelling to some degree in his manuscripts and to a greater degree in his prints. Nonetheless, it is clear from his rhymes and from his uncorrected manuscripts that his pronunciation, even in his "English" poems, remained broadly faithful to the Scots words that the anglicized spelling stood for; and his grammar, even when his printers "corrected" his manuscripts, rarely strayed far from that of Dunbar. This explains Ramsay's enigmatic statement referring to his "English" poems: "Tho' the words be pure English, the idiom or phraseology is still Scots."

To illustrate this point, transcriptions of the fables into modern Scots orthography are included here and form the basis of our readings (which are performed aptly enough by a young Edinburgh political moralist with family roots in England).